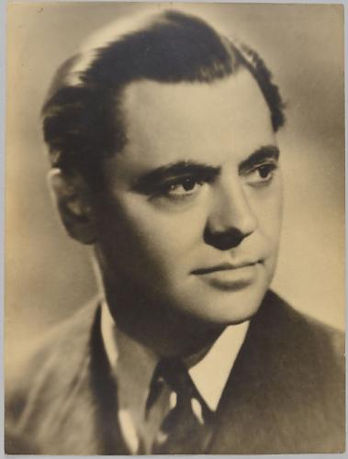

Jean Moulin became the face of the French resistance and a symbol of freedom. Across France there are schools, colleges and streets named in his honour. However outside of France he is relatively unknown.

1899-1938

Jean Moulin was born in 1899 in Béziers, Occitanie, to Antoine and Blanche Moulin. Moulin grew up in a Republican ‘left wing’ family. His father was a teacher and a member of the radical-socialist party, whose political views and strong beliefs in freedom and justice spread to his three children. His father actively encouraged him to enter a career in politics. Moulin studied at the Lycée Henri-IV in Béziers before going on to study law in Montpellier in 1917. Despite proving himself to be an average student, he began his role in prefectural administration when he was appointed to the prefect of the Hérault department’s office, while still undertaking his studies.

His role would be interrupted in April 1918, when Moulin became old enough to join the fight in the First World War. After completing his training, he was assigned to the 2nd Engineer Regiment and sent to the Vosges region of France in September. However, Moulin’s military career would be a short one. The armistice was signed on 11th November 1918 and he never saw action. Following his demobilisation in 1919, he returned to his position in the Hérault region before being appointed to the role of private secretary in 1920.

Moulin enjoyed sport, in particular skiing but it was his passion for art, which he inherited from his father, that was to be a central part of his life. At the age of sixteen his artworks were first published in newspapers such as the left-wing ‘La Guerre Sociale’ and satirical newspaper ‘La Baionnette’. Once he began his political career, he began signing his work under the pseudonym ‘Romanin’. Some of his later works would include anti-Nazi and anti-Fascist drawings.

In 1924 he was appointed deputy prefect in the subprefecture of Albertville in south-east France. He remained in this position until 1930 when he was promoted to the role of deputy prefect, second-class, in Chateaulin, Brittany. In 1932, in a career shift, Moulin took a position in the office of Radical-Socialist party member and undersecretary of State for Foreign Affairs, Pierre Cot. While working with Cot, Moulin provided help to Spanish Republicans fight the pro-Franco forces, In January 1937, at the age of 38, Moulin became the youngest prefect in France, when he was appointed prefect of Aveyron, in the Occitanie, where he remained until 1939.

1939-1943

On 1st September 1939, Germany forces invaded Poland. Two days later, France and Great Britain declared war on Germany. Jean Moulin had only recently been made prefect in Chartres, 90km southwest of Paris, when war was declared. He quickly began putting defence and mobilization measures in place.

What followed was known as the ‘Phoney War.’ German forces did not make a move until April 1940, when they invaded Norway and Denmark. In May, German forces made their move into the Netherlands, then quickly advanced through Belgium, Luxembourg, and Northern France via the Ardennes Forest. By 4th June, German forces had taken ports on the French and Belgian coast. Following the Allied evacuation from Dunkirk, the fall of France was seemingly inevitable. On 14th June, German Forces entered Paris, which had been declared an open city.

Moulin later wrote that Chartres was being bombarded and with the arrival of the occupiers in Paris, administrative structure had already begun to collapse and many civilians were in fear. With the city of Chartres being so close to the capital, Jean Moulin began to witness what became known as the ‘Exodus.’ Thousands of people began fleeing Paris and northern France attempting to find safety in the south. However, the men and women of Chartres had begun to leave the city in anticipation of what was to come. This included shopkeepers and bakers and those who provide essential services such as police, doctors, and firemen. Moulin later wrote;

‘If Chartres is almost empty of its inhabitants, the monstrous flood from the Paris region still pours heavily into the city.’

As a result, Moulin had to continue to try to maintain order by preventing theft and looting, while also trying to provide help to those fleeing. He began organising the storage of canned goods and bread that could then be distributed as well as succeeding in finding resources to provide 172,000 meals to civilians.

On 16th June 1940, German forces entered the city of Chartres. The following day, Moulin, who had remained at his post, was summoned by a German officer. It was demanded that he sign a declaration stating that Senegalese troops, who had been protecting the area, had raped, and killed women and children in the local area. The reality was that these civilians had been killed by German bombardment. Moulin refused to sign the document. He was beaten but told the German officer;

‘No, I will not sign. You know very well that I can’t put my signature at the bottom of a text which dishonours the French Army.’

As a result, his torture continued and he was held prisoner in a small room alongside the body of a woman who had been killed. German command in the town hoped that this would be enough for him to cave in and participate in their lie. Moulin, fearing that he would break under torture, attempted suicide by cutting his throat with a piece of glass. When he was discovered, he was taken by a German doctor to hospital where he recovered before he returned to his post in administration. For the rest of his life, he wore a scarf around his neck to hide his scar. On the same day that Moulin had made his first brave act of resistance, Maréchal Petain, Chief of State, requested an armistice with the German occupiers. This was signed on 22nd June 1940, in the Forest of Compiegne, where the armistice ending the First World War had been signed nearly twenty-two years earlier.

The following day from his exile in London, General Charles de Gaulle, who formed and lead the French National Committee (CNF), issued his appeal to the people of France. De Gaulle’s BBC broadcast from London stated; ‘Whatever happens, the flame of French resistance must not and shall not die.’

Jean Moulin remained in his position as Prefect within the Vichy government for several months, attempting to look after those under his care as best he could. However, he was soon dismissed by the Vichy regime and then, on 2nd November, he was removed from his office altogether. He briefly returned to Paris before moving to the south of France where he began his moves towards his involvement with early resistance movements. It was while visiting family, possibly in Montpellier that Moulin wrote his diary, ‘Premier Combat’ in which he told of his ordeal in Chartres. He then went to live with family in Saint Andiol. It was here and in Marseilles where Moulin began making connections with early resistance movements that were growing in the south. He met with the head of the ‘Mouvement de la Liberation Nationale’, Henri Frenay and later with Francois de Menthol, a law professor from Lyon who founded the Liberte Movement. He travelled to Paris to connect with resistance movements which had formed in the capital, although this seemingly had little success at the time.

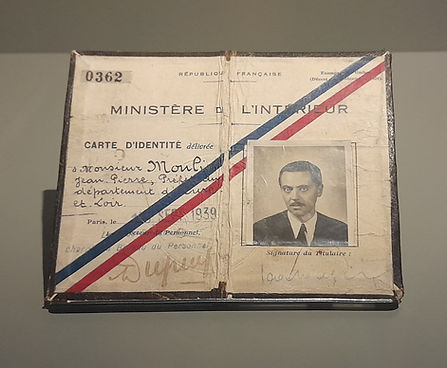

At some point during his time in the south, Jean Moulin had obtained a forged identity card under the name of ‘Joseph Mercier.’ He potentially had the option go to the United States or he could travel to England to join De Gaulle’s movement. Armed with useful information regarding resistance movements springing up across France, he decided the latter option was the best way he could continue to serve his country. He travelled to Portugal where he met with the British Secret Service (SIS) before he continued travelling to London. On 25th October 1941, Jean Moulin first met with Charles de Gaulle. Moulin presented him with the information he had gathered on the fledgling resistance movements and their members in the Southern Zone. Charles De Gaulle was impressed and saw the benefit of using him on the ground in France. Jean Moulin was a skilled listener and organiser and his career had allowed him to travel around France giving him an excellent understanding of different people, different needs and different backgrounds. Likewise, Moulin was aware that working with the support of De Gaulle was the best way to make a difference.

De Gaulle made him a delegate of the CNF in the Southern Zone. Moulin soon began learning how to code and de-code information and started parachute training. On 1st January 1942, Jean Moulin, now using the alias’s ‘Rex’, or ‘Max’ was parachuted into Provence under the cover of darkness. He was tasked with unifying resistance movements in the south and encouraging members to join up with De Gaulle’s cause, to create a strong, coherent network that could effectively disrupt the occupiers. He landed in France with his orders, photographs, money, and other information, concealed in a small matchbox.

Moulin set up headquarters in Lyon, in the free zone, and began his work of connecting, unifying, and coordinating the three significant resistance movements in the south. These resistance movements were; Combat-lead by Herni Frenay, Franc-Tireue– lead by Jean-Pierre Levy and Libération– lead by Emmanuel d’astier de la Vigerie. Moulin had much difficulty in unifying these groups. They views ranged across the political spectrum, including communism and nationalism. They also wanted to remain independent from the French government in London. However, Moulin succeeded in January 1943 in creating the ‘Mouvements Unis de la Rèsistance’ (MUR), which was the first step in persuading these groups that unifying with the backing of the exiled French government, was the best way to resist the German occupiers.

In February 1943, Jean Moulin returned to London where he updated De Gaulle on progress of his mission. Jean Moulin believed that he could succeed in unifying resistance movements across France, not just in the free zone. Charles de Gaulle made him Minister of the Comité Nationale and Moulin returned to France to complete his mission. His links to the art world enabled him to pose as an art dealer and in early 1943 he opened his art gallery in Nice, where he exhibited his own art.

Once again there was much opposition from resistance movements to unifying themselves, alongside various political parties, under de Gaulle. This idea was not initially welcomed by many resistance leaders. Once more Moulin succeeded in persuading these movements that they all ultimately wanted a liberated, free France and that this was the best way to make that happen. In Paris, on 27th May 1943, at 48 Rue de Four in the 6th arrondissement, Jean Moulin chaired the first meeting of the ‘Counseil National de la Rèsistance’ (CNR). The meeting included resistance leaders from across occupied and unoccupied France. Following the meeting, Charles de Gaulle was seen as the head of the resistance in France.

During a meeting on 21st June 1943, Jean Moulin was arrested with other members of the resistance in Caluire-et-Cuire near Lyon. He was tortured by the Chief of the Gestapo, Klaus Barbie, also known as ‘the butcher of Lyon.’ Moulin refused to give any information and as a result he was taken to Paris and tortured further. He refused to break. Severely tortured, he was placed on a train heading for Germany. Sadly, Jean Moulin would not survive the journey and died on 8th July 1943, somewhere near Metz railway station. Jean Moulin’s sister Laurie received a letter after the war, dated 9th July 1943, which stated that an unknown body had been cremated by French police near Metz. In 1946, in a ceremony in Béziers, Laurie was presented with her brother’s Military medal and the Croix de Guerre.

On 19th December 1964, Jean Moulin’s ashes were transferred to the Pantheon in Paris where he was finally laid to rest. The ceremony was attended by members of the public as well as soldiers, former resistance members, dignitaries and politicians including Charles de Gaulle and the Minister of Cultural Affairs, André Malraux. In his speech Malraux said Moulin was;

‘Parachuted onto the soil of Provence, to become leader of the people of the night.’

For his actions, bravery and strong belief in freedom, Jean Moulin was, and remains, a hero of the French Republic and a symbol of the French resistance.

Leave a comment